H5N1 Bird Flu

See just this Post & Comments / 1 Comments so far / Post a Comment / HomeMonday, March 27, 2006

Fatima Mohammed Yussef, 30, from Qaliubiya, north of Cairo - second Egyptian fatality, fifth case. Suspected case in Baghdad too.

Fatima Mohammed Yussef, 30, from Qaliubiya, north of Cairo - second Egyptian fatality, fifth case. Suspected case in Baghdad too.Saturday, March 18, 2006

Friday, March 17, 2006

Five more countries reported in the Globe today: Denmark, Israel, Afghanistan, India, and Myanmar.

I guess the business of culling and burning the bird bodies is around preventing them from being consumed. Is the virus not killed by cooking?

Friday, March 3, 2006:

The best possible individual outcome is to catch this disease (if and when it spreads to humans) and then survive. Otherwise you can wash your hands and cover your mouth when you sneeze. That's it. The rest is ineffectual posturing on the part of politicians and lackey scientists.

Saturday, February 18, 2006:

Now India and France. Well, we know it is going everywhere don't we?

Sunday, February 12, 2006:

Infected birds dying in Nigeria, Azerbaijan, Greece, Italy.

They are being very careful with the carcases; but I think it takes more than picking up a bird with your bare hands to catch it, doesn't it? Maybe if you pick up a bird and you have a scratch, or you pick it up and then wipe your eyes?

Friday, January 13, 2006:

Spiegel: Mutation Could Help Virus Spread to Humans

Thursday, January 5, 2006:

Second Turkish teen dies of bird flu

It's back, this time in Turkey. They have airports in Turkey, and easier access to them than in China, no? But wait ... these are still transmissions from Bird to Human, not Human to Human.

Picture from Reuters - Turkish veterinary officials in protective suits collect poultry from the residents in snow covered eastern city of Erzurum in Turkey January 4, 2006. A second Turkish child died from bird flu on Thursday, officials and doctors said, in the first human cases of the disease outside China and Southeast Asia. Picture taken January 4, 2006.

Picture from Reuters - Turkish veterinary officials in protective suits collect poultry from the residents in snow covered eastern city of Erzurum in Turkey January 4, 2006. A second Turkish child died from bird flu on Thursday, officials and doctors said, in the first human cases of the disease outside China and Southeast Asia. Picture taken January 4, 2006.Monday, November 28:

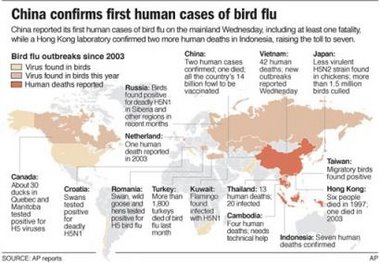

Toronto Star - Travellers to China face bird flu screening

Shanghai, China - Shanghai began screening international passengers for fevers or other symptoms of bird flu Monday, as World Health Organization experts began investigating two deaths from the disease among farmers in eastern China.

At Shanghai's Pudong International Airport, all passengers leaving or entering the country now must complete a health declaration form that asks if travellers have had close contact with poultry, birds, bird flu patients or suspected cases over the past week and whether they have symptoms like fever, coughing and shortness of breath.

Passengers with temperatures exceeding 38 C would be further examined. Those who recently visited bird flu-affected areas or had contact with birds or poultry would have to undergo treatment at a designated hospital, the official Xinhua News Agency said.

The precautions, announced in a notice on the government's website, are similar to those imposed during the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which — unlike bird flu — spread easily from person to person. The World Health Organization says the main route of human infection by the H5N1 bird flu virus is direct contact with infected birds, and that transmission from person to person requires very close contact with an ill person.

A team of four WHO experts began an investigation in the eastern province of Anhui, where two female farmers died of the disease, said Roy Wadia, a spokesman from the WHO's Beijing office. The two are the country's only confirmed bird flu deaths. The only other confirmed bird flu victim survived. The experts will visit Zongyang and Xiuning counties — about 100 kilometres apart — and see whether procedures for surveillance and diagnosis for the cases were carried out properly, Wadia said.

China's Health Ministry said analysis of the human cases found the virulent H5N1 strain of the virus had mutated compared with the strain found in Vietnam but couldn't be passed from person to person, Xinhua reported. It didn't elaborate.

The WHO's infectious diseases specialist in Beijing, Dr. Julie Hall, said viruses mutate all the time and there was no need to panic — though her agency would seek more information from the Chinese government.

A 24-year-old woman from Zongyang developed fever and pneumonia-like symptoms on Nov. 1 after being in contact with sick chickens and ducks. She died nine days later, the first confirmed human fatality in China. The second woman, a 35-year-old from Xiuning, died Nov. 22 of the same symptoms after handling infected poultry.

China, which has the world's largest number of chickens, has called bird flu a "serious epidemic." It has reported 22 outbreaks among poultry in recent weeks, and millions of poultry have died or been killed in an effort to control the disease.

On Monday, China's central bank ordered financial institutions to provide loans for companies affected by the bird flu outbreaks, such as poultry and egg farmers, wholesalers, retailers, processors and feed companies, and to exempt them from fees for overdue payments. Such support for companies is needed "to ensure economic and social stability," said the notice posted on the website of the People's Bank of China. China's communist leaders also have moved to boost financial support to the more than 50 million farm households that raise poultry, partly to help ensure that farmers do not cover up cases because of worries over financial losses.

The overall economic impact of the outbreaks among the country's poultry industry is likely to be limited, Andy Rothman, a Shanghai-based strategist for CLSA Asia Pacific Markets, said in a report issued Monday. He noted that although huge, the poultry industry accounts for only about three per cent of China's gross domestic product and 0.25 per cent of its exports.

Sunday, November 27:

This picture was taken by Thomas Mukoya for Reuters. It shows Marabou storks standing on top of a garbage dump in the outskirts of Nairobi. The caption says "Scientists are worried that the large numbers of wild and domestic birds living in close proximity to human populations in Africa could spark uncontrollable outbreaks of bird flu on the continent. Marabou storks are scavengers and can be found around urban refuse dumps as well as on the open plains."

This picture was taken by Thomas Mukoya for Reuters. It shows Marabou storks standing on top of a garbage dump in the outskirts of Nairobi. The caption says "Scientists are worried that the large numbers of wild and domestic birds living in close proximity to human populations in Africa could spark uncontrollable outbreaks of bird flu on the continent. Marabou storks are scavengers and can be found around urban refuse dumps as well as on the open plains."The business of culling bird flocks, domestic or wild, seems to me to be a lunatic exercise. Somebody tell me I am wrong? The virus cannot be stamped out in bird populations by these or any other means. What are you going to do? Test every wild population? Nonsense. Furthermore, the virus may be extremely effective and kill many or even most of the birds that it infects, but it is never going to kill them all, a bio-engineered virus might possibly hit 100% mortality, but this one is not as far as we know human-engineered. And it mutates anyway. So somewhere there is a healthy bird which is carrying the virus. QED.

Ridiculous!

Saturday, November 26:

China confirms second human death from bird flu

Thursday, November 17:

Indonesia Confirms New Flu Deaths

(AP) Indonesia on Thursday confirmed bird flu has killed two more people, raising that country's total deaths to seven.

WHO warns of more China bird flu outbreaks

Beijing (Reuters) - China is likely to suffer more outbreaks of bird flu among poultry and possibly people in coming winter months, a WHO official said on Thursday after China confirmed its first cases of human infection.

The Coming Pandemic - Gwynne Dyer - 1 June 2005

The long-term solution is to invest many billions of dollars and a huge amount of political capital in persuading peasant families throughout China and South-East Asia to change the way they raise their poultry. The urgent short-term task is to develop a way of mass-producing influenza vaccine far faster than is now possible. It's urgent because "the world is in the gravest possible danger of a global pandemic," as Dr Shigeru Omi, Western Pacific regional director of the World Health Organisation, told an emergency conference on avian flu held in Vietnam two months ago.

The H5N1 avian flu virus first crossed into human beings in 1997, but it has clearly been mutating in recent years in ways that make it more capable of moving from birds to people. The spate of human infections in mid 2003 in China and South-East Asia was so serious that over 100 million domestic birds were killed or died in those countries before it subsided in early 2004, but there was only a few months' respite before bird-to-human transmission began again last June.

The virus has now appeared in wild birds who can carry the virus far beyond its original reservoir in domestic chickens in southern China and South-East Asia: in late May China closed all its nature parks after 178 migratory geese were found dead from the virus in Qinghai province in the north-west. The most recent outbreak has so far killed 53 people in Vietnam, Thailand and Cambodia -- and even more ominously, the first probable case of human-to-human transmission was recorded last September in Vietnam.

The danger of a global flu pandemic that could be as bad as or worse than the "Spanish influenza'outbreak of 1918-19 (which killed 40 to 50 million people, half of them young, healthy adults) comes from the fact that a strain of influenza virus that normally affects only birds can swap genes with a strain that is highly infectious between human beings. If people with the human type of influenza should also be infected with the avian type (through direct contact with infected poultry), the gene swap can easily occur -- and direct human-to-human transmission becomes possible. At that point, given current patterns of international travel, the world might be only weeks away from a global pandemic.

We don't know if avian flu viruses swapping genes with human types caused the lethal Spanish influenza, but that was certainly the source of the much milder "Asian flu" outbreak in 1957-58 (which killed 70,000 people in the United States alone) and the "Hong Kong flu" pandemic in 1968-69 (50,000 US deaths). Given the rate at which influenza viruses mutate, we are overdue for another pandemic -- and this one could be a monster.

The H5N1 virus is resistant to most anti-viral drugs, and in the avian form it has been getting steadily stronger. Early outbreaks killed around 10 percent of poultry flocks; more recent ones have been killing up to 90 percent.

In people who have caught avian flu, the death rate has been horrendous: 50 to 75 percent of those infected. A gene-swapped version that is directly communicable between human beings might be less lethal, but it could still far exceed the 1-2 percent fatality rate of the Spanish influenza. To make matters worse, this version of avian flu has a long incubation period. Unlike the SARS virus that killed 774 people two years ago, it may be very hard to stop before it spreads into the general population.

"When people were transmitting the (SARS) virus they were already showing signs, so it could be picked up at airports with temperature (detectors)," explained World Health Organisation spokesman Peter Cordingley. "With (avian) flu you can be infectious before you show any signs." If human-to-human infections start to spread, there could be not only huge loss of life, but global economic chaos as air travel is shut down to contain the spread, borders are closed, and essential services break down because too many of their workers are off sick or just hiding from the flu at home.

Governments are already arming themselves to deal with this pandemic -- on 1 April President George W. Bush added "influenza caused by novel or reemergent influenza viruses that are causing, or have the potential to cause, a pandemic" to the list of diseases for which a quarantine can be declared -- but there is no vaccine. As things stand now, none could be available for months after the pandemic begins. That is why five teams of scientists, writing in last week's edition of the journal "Nature", urged a permanent global task force to react quickly to outbreaks of bird flu. If it is not done, they warned, millions will die.

The first opportunity to create such a task force will be at the G-8 summit in Scotland next month, and its first priority must be to develop new and easily produced vaccines to deal with the expected outbreak. But lasting progress, as Dr Samuel Jutzi of the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation said at the Vietnam meeting in March, depends on "addressing the transmission of the virus where it occurs, in poultry, specifically free-range chickens and wetland-dwelling ducks." In other words, a couple of hundred million Asian peasants have to be persuaded to stop living in the same space as their poultry. A tall order, but a necessary one.

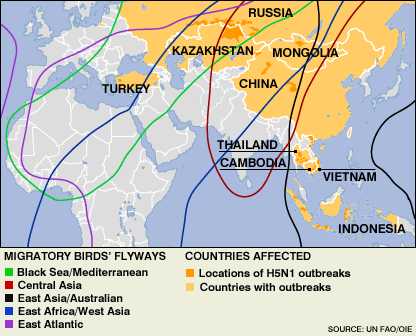

Sorry, I could not find a larger picture of this map.

Preventing Pandemics - By Gwynne Dyer - 13 October 2005

It would be funny if it were not so serious. As migratory birds carry the avian influenza virus west across Europe, Britain is following in the footsteps of Russia, Ukraine, Romania and Turkey and asking hunters to shoot down as many incoming ducks and geese as possible. They have been issued with bird-flu testing kits to see if their victims are carrying the dreaded virus, but they really have little to worry about: all the cases of direct bird-to-human infection, now over a hundred in total, have occurred on family farms in South-East Asia.

The panic over bird flu is not wholly misplaced. If the H5N1 strain that is currently ravaging wild bird flocks learns to pass between human beings easily while retaining even a tenth of its current lethality -- the death-rate among people who catch it directly from birds has been as high as 50 percent -- the world would face an influenza pandemic as grave as the one in 1918-19. That one, known as the "Spanish influenza", killed between fifty and a hundred million people at a time when the world's population was only a third of what it is now.

Recent research has shown that the 1918 virus was also a purely avian strain that jumped to human beings, but then changed enough to become highly infectious between people. Its peculiar pattern of mortality, with a much higher death rate than usual among healthy young adults (half the victims of the Spanish flu pandemic were between 18 and 40 years old), is reappearing in the cases of direct bird-to-human transmission of the past two years. If the current avian virus also develops the ability to move easily between people, the world is in trouble.

Only in the past couple of decades has it been widely understood that almost all the quick-killer infectious diseases that have emerged to ravage human populations since the rise of civilisation come from our own domestic animals. Human beings in the wild, like other predators that live in small, isolated groups of a few dozen individuals or less, would rarely have fallen victim to the quick-killer viruses and bacteria whose natural habitat is animals that live in large herds.

Even if such a disease did jump from some prey animal to the hunters who killed it, and even if it then adapted enough to infect the other members of the hunter-gatherer band, the new, human-infectious form would usually die out when it had run through those few dozen people. Only when civilisation brought people together in large groups, and those people began living in constant close contact with domesticated versions of herd-dwelling animals, did the quick-killer diseases that often devastate those species begin to adapt permanently to the human species.

Over the past three or four thousand years this process has given us a whole range of highly infectious new human diseases, including quite lethal ones like smallpox, cholera, typhoid, and the Black Plague. Influenza, which colonised civilised human beings via their flocks of domesticated birds, is usually a relatively mild member of this family of diseases, but the flu virus mutates with great ease, and occasionally it assumes a highly lethal form.

As our population has grown into the billions and the volume and speed of travel have soared, we have become more vulnerable to these "emergent" diseases, but they are unlikely to emerge on a British or even a Russian farm. Eighty years ago the "Spanish influenza" virus probably made its way from wild ducks into chickens and thence into human beings on a Kansas farm, but modern commercial farming does not involve people and their animals sharing the same living spaces. Moreover, if some disease does cross the species barrier anyway, its human victims are far more likely to get early treatment (and, if necessary, quarantine).

The places where the style of farming and the density of human and animal populations still favour the easy movement of diseases from animals into people are mostly in Asia, particularly in South-East Asia. That is where all the new flu viruses have emerged in the past half-century, where the SARS virus came from two years ago, and where other emergent diseases are most likely to appear. As a first step, it would make sense to create a network of trained observers who would report on any unusual disease patterns among the local farm families or their animals.

This is being done in Thailand, and much poorer Vietnam is making a start, but Indonesia has done little, the Chinese refuse to say what they are doing, and some of the smaller countries have done nothing. The developed countries would be wise to support these reporting networks, since they offer the best chance of stopping a new disease before it reaches the rest of the world.

In the longer run, farmers throughout the region must be encouraged to change their long-established ways of raising poultry, pigs and other animals. That is a tall order, but similar shifts in farming practice have already happened elsewhere, and at least the region's economy is developing fast enough that it can provide markets for a more commercial style of farming and non-farm jobs for those no longer needed on the land.

The countryside wouldn't be nearly so picturesque at the end of the process, but the world wouldn't be facing so many new diseases, either.

Infection, The usual suspects - The Economist - November 17 2005

Some of the efforts to control bird flu could be usefully extended to tackle other emerging human diseases that come from animals.

ONE billion dollars is a lot more than chicken feed. But this is what the World Bank believes is necessary to spend on controlling bird flu. Last week in Geneva, representatives from more than 100 nations seemed to agree; and hundreds of millions of dollars are likely to be pledged at a meeting in China next January.

So far, there have been just 64 confirmed human deaths from bird flu, although China this week announced that a further two people had died from the disease. Bird flu has been more costly to industry. The Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates the economic impact has been more than $10 billion. Samuel Jutzi, director of its animal-production and health division, says that a single large outbreak in 2004 cut GDP across South-East Asia by up to 1.5%.

What is focusing the minds of many at the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank are fears over what the costs might be if the virus were to turn into something that humans could easily transmit to one another. SARS, which killed 800 people, caused an economic loss of around 2% of East Asian regional GDP in the second quarter of 2003, according to a report from the Bank on November 8th. That is about $200 billion.

While it is impossible to predict the precise nature of the next influenza pandemic—an event that occurs about three times a century—it could last for up to a year. Milan Brahmbhatt, the Bank's leading economist for East Asia and the Pacific, therefore suggests that it might cost at least $800 billion.

Clearly, then, it is important to bring this strain of bird flu under control. The threat of an influenza pandemic will be reduced by the improvements in viral-strain surveillance, veterinary health care and laboratory services that are being proposed for bird flu.

The bigger picture:

But it is also worth taking a broader look at diseases emerging from animals. The World Bank thinks it makes sense to take long-term measures to strengthen the institutional, regulatory and technical capacity for dealing with animal as well as human health because there are such a large number of animal-related pathogens emerging across the world.

Science has thus far counted 1,400 pathogens that affect humans. Mark Woolhouse and Sonya Gowtage-Sequeria from the University of Edinburgh have surveyed these and found that 13% are regarded as emerging (such as SARS or HIV) or re-emerging (such as tuberculosis, West Nile virus or malaria). Furthermore, the number of new pathogens emerging seems to be on the increase.

Dr Woolhouse argues that new pathogens cannot have been accumulating at the rate they are currently being discovered (one or two per year) because otherwise the world would be overrun with them. So either many of these new pathogens are flashes in the pan that will disappear as fast as they appear, or something different is going on in modern times.

Peter Daszak, of the Wildlife Trust in New York, also thinks that emerging diseases are on the increase. Research by Dr Daszak, in collaboration with researchers from Columbia University, shows that human pathogens have emerged or re-emerged 409 times in the past 50 years. There is a steep rise in such events over the decades—a trend that remained even when the group corrected the data for greater reporting in recent times.

Both researchers observe that most of these diseases come from animals; such diseases are known as zoonoses. Many are important because they are so lethal (Ebola is one such example). Furthermore, in a paper shortly to appear in the Journal of NeuroVirology, Dr Daszak and Kevin Olival, a biologist at Columbia University, will say that these new viruses tend to be serious. Half of the emerging viruses are characterised by inflammation of the brain or serious neurological symptoms.

Broadly speaking, it is change that is driving this emergence, whether that change takes place in human travel, agriculture, land use or the environment. Dr Woolhouse says the world is changing very fast in “ways that matter to pathogens and ways that give them new opportunities to infect new host species or get to new areas.” For example, people are travelling more between tropical and other regions. West Nile virus arrived in America in 1999 in New York. International travel led to the global spread of SARS in 2002.

Another driver is the rapid intensification of agriculture, now increasing in developing countries. Avian influenza is one example of a zoonosis associated with such intensification, as too are BSE in cattle, salmonella in chickens, Nipah virus in pigs and antibiotic resistance in food-borne bacteria. Other factors include urbanisation, the overcrowding of humans in poor, tropical countries and the movement and trade of animals.

Still, about half of the zoonotic pathogens have a wildlife reservoir. These can be spread by changes in land use that bring humans into closer and more regular contact with wild animals. Landscape fragmentation and ranching have been linked with Lyme disease and brucellosis, says Dr Daszak. The Nipah virus is naturally found in bats but seems to have moved to Malaysian pigs with changes in stocking density. It has killed around 40% of the 265 people it has infected.

SARS, too, had an animal origin. In a recent paper in Science, a team of researchers led by Wendong Li at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing identified bats as the probable source. It is possible that bats were kept in the same live animal market in Guangzhou, China, where palm civets were also found to be carrying the SARS virus. A densely packed, mixed animal market where wildlife, domestic animals and humans mingle in less than sanitary conditions provides the ideal conditions for a virus to jump from one species to another.

If many of the factors responsible for the emergence of new diseases—such as international travel, intensification of agriculture and urbanisation—are likely to continue, how is the world to respond to the threat of new diseases? The answer seems to be to spend more money on animal and human health, as well as on the monitoring and surveillance of pathogens. With the world an increasingly connected place, achieving high standards in these areas would be a global public good.

Tuesday, November 1:

Tuesday, November 1:A convenient pandemic might save him, and failing that, maybe just the rumour that it is 'time' for a pandemic might do it - do ya think? A-and then an opportunity for a Son-of-Patriot-Act to enforce quarantine, restrict travel, with, who knows ... a mandatory quota of 'volunteers' for testing by the drug companies?

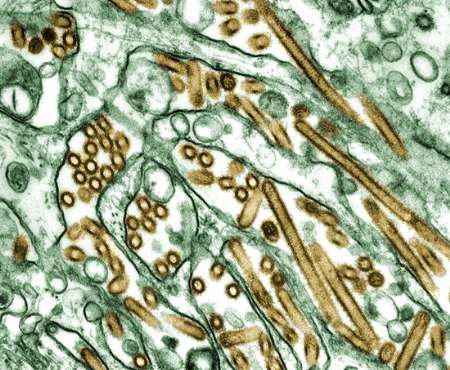

Photomicrograph 150,000 x enlargement. Absolute dimensions? ... dunno, what would it be? 5-10 Angstroms x 200 Angstroms? Anybody know? It is the golden bits in the electron micrograph below that are H5N1.

Photomicrograph 150,000 x enlargement. Absolute dimensions? ... dunno, what would it be? 5-10 Angstroms x 200 Angstroms? Anybody know? It is the golden bits in the electron micrograph below that are H5N1.

Thursday, October 27:

Nature - Migration threatens to send flu south

Problem is, this is a "Premium" site - I will post the whole article as a comment. Mass migration: red outlines show flyways of the Garganey duck, a species at high risk of spreading the H5N1 virus. The birds breed in the north in summer (dark orange) and then fly south for the winter.

Problem is, this is a "Premium" site - I will post the whole article as a comment. Mass migration: red outlines show flyways of the Garganey duck, a species at high risk of spreading the H5N1 virus. The birds breed in the north in summer (dark orange) and then fly south for the winter.The story is so full of "may". The virus may mutate. An easier transmission from birds to humans may develop. Transmission between humans may be possible in the future. And meanwhile the boys are selling the internet equivalent of newspapers except you can`t wrap fish in it. Let`s call it a zeit-ripple.

The only thing you can actually DO is wash your hands regularly and with soap. The official Halliburton safety guideline and Rule of Thumb is to wash for as long as it takes you to hum a verse of "Happy Birthday to you ...". When we make the Dr. Strangelove version this detail will be included for comic relief. The efficacy of vaccines and medicines? I don`t know. If I did know would I get some? Again, dunno, can`t say. Speaking of medicines, Mr. Martin has got that special H look, and his colleague appears to be asleep on his shoulder, ho-hum, what-ever.

The only thing you can actually DO is wash your hands regularly and with soap. The official Halliburton safety guideline and Rule of Thumb is to wash for as long as it takes you to hum a verse of "Happy Birthday to you ...". When we make the Dr. Strangelove version this detail will be included for comic relief. The efficacy of vaccines and medicines? I don`t know. If I did know would I get some? Again, dunno, can`t say. Speaking of medicines, Mr. Martin has got that special H look, and his colleague appears to be asleep on his shoulder, ho-hum, what-ever.Wednesday, October 26:

in Canada - a Conference or just a photo op?:

Yahoo - Countries Discuss Bird Flu Preparations

Canada's Prime Minister, Paul Martin, seemed mostly concerned with tactics to minimize panic and social disruption. There are two obvious approaches to this: control the news, spin it and conceal it; or tell the truth and help people deal with it. Singapore explicitly favours the second having witnessed and analysed Indonesia's head-in-the-sand fiasco over the past few years. Which way a government swings on this would depend upon how they view their countrymen I suppose ...

Reuters - Fresh bird flu outbreak in China

Reuters - French trio tested for bird flu after Thai zoo trip

Tuesday, October 25:

CBS - Bird Flu's Human Toll Increases

CNN - Global alert from bird flu intensifies

CTV - Dead parrot had H5N1 bird flu: Britain

CTV - Experts to convene bird flu summit in Canada

Medical News Today - Bird flu statistics 1959-2003

Several of the largest outbreaks (Pennsylvania, Mexico, Italy) initially began with mild illness in poultry. When the virus was allowed to continue circulating in poultry, it eventually mutated (within 6 to 9 months) into a highly pathogenic form with a mortality ratio approaching 100%. Moreover, the initial presence of low-pathogenicity virus in these outbreaks complicated diagnosis of the highly pathogenic form.

IOL South Africa - Fourth bird flu victim dies in Indonesia

Indonesia confirmed on Tuesday that a fourth person in the country had died of bird flu, while China said hundreds of farm geese had died in the latest outbreak of a disease that seems to defy efforts to halt its spread.

Singapore Poster in English / Chinese / Malay / Tamil

Economist - The spreading bird-flu menace reaches Europe (Oct 20)

Reuters - US mulls federal troops for bird flu quarantine (Oct 12)

Monday, October 24:

In 2003 there was a SARS 'outbreak' in Toronto, exclusively among a handful of health care workers as I remember. I was travelling from Brasil to Canada at the time and had a smoker's cough, on account of which I was shunted into a separate lineup at customs. After a half-hour wait my ear temperature was taken. Thank God I was not running a fever - after 10 hours crammed into an economy seat I easily could have been! No telling what might have happened ...

This bird flu is evidently already ubiquitous among birds the world over. At the moment, transmission to humans is relatively difficult, and transmission between humans is unlikely ('contact' seems to mean fecal/oral). This could change - if it drifts or shifts such that transmission is easier, things could get interesting.

The H5N1 strain remained largely in South-East Asia until this summer, when Russia and Kazakhstan both reported outbreaks. Scientists fear it may be carried by migrating birds to Europe and Africa but say it is hard to prove a direct link with bird migration. Reported transmission to humans is so far exclusively through contact with infected birds. The viruses will almost certainly change through the mechanisms of drift or shift or both, and transmission between humans may become possible either by direct contact, or through airborne droplets - anything is possible.

The H5N1 strain remained largely in South-East Asia until this summer, when Russia and Kazakhstan both reported outbreaks. Scientists fear it may be carried by migrating birds to Europe and Africa but say it is hard to prove a direct link with bird migration. Reported transmission to humans is so far exclusively through contact with infected birds. The viruses will almost certainly change through the mechanisms of drift or shift or both, and transmission between humans may become possible either by direct contact, or through airborne droplets - anything is possible.Official Lies:

US - Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC)

UN - World Health Organization (WHO)

UN - Food & Agriculture Organization (FAO / AGA) - maps

EEC - European Influenza Surveillance Scheme (EISS)

Canada - Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention & Control (CIDPC)

Singapore - Ministry of Health (MOH & AVA)

England - Department of Health (DH)

Classification & Nomenclature:

Avian influenza - AI

Types: A, B, C, apparently according to degree of danger (?).

Subtypes by surface proteins: hemagglutinin - HA (16) and neuraminidase - NA (9), and Strains. H5N1 is Type A, HA Subtype 5, NA Subtype 1.

Pathogenicity: high or low, either among birds or humans.

Change by antigenic drift (gradual) & shift (abrupt).

Used as adjective or noun:

Pandemic: Of a disease: epidemic over a very large area; affecting a large proportion of a population.

Epidemic: Of a disease: Prevalent among a people or a community at a special time, and produced by some special causes not generally present in the affected locality.

Beans: Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia.

First Wave: October 2003 - May 2004, 35 cases, 24 deaths.

Second Wave: June 2004 - October 2004, 9 cases, 8 deaths.

Third Wave: December 2004 - October 2005, 74 cases, 29 deaths.

There is apparently some divergence on what constitutes a `wave`.

Down.

Nature - 26 October 2005

Migration threatens to send flu south

Researchers fear that the bird flu virus's next stop will be Africa, where dependence on poultry means that the consequences could be even worse than in southeast Asia.

The deadly H5N1 bird flu virus is expected to be carried by birds into the Middle East and east Africa within weeks, the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) warned last week.

Concern is growing that the Rift Valley in east Africa is particularly at risk. Researchers told Nature that if the virus reaches the area's lakes, the health and economic consequences could be even worse than in southeast Asia, where the virus is endemic in many regions.

"The next step we expect the virus to take is into Africa, because that is on the main migratory route for birds," says Ward Hagemeijer of conservation organization Wetlands International in Wageningen, the Netherlands. "The first birds are already in east Africa." There is no definitive evidence that migratory birds are carrying the disease, he says, but the pattern of the virus's spread points strongly to wildfowl travelling southwest from northern Russia to east Africa.

Outbreaks have already occurred along the route in Romania and Turkey, where they seem to have been controlled by culls and quarantine orders. But the migration is now in full swing, and some birds have crossed the Middle East and reached the Rift Valley. Middle Eastern states have stepped up efforts to plan for possible outbreaks, and some are monitoring migrating birds, but there has been little response in more vulnerable east African countries. This means that if the virus arrives there, it could quickly become endemic.

"The impact in Africa will be dramatically different from the impact in Europe," says Hagemeijer. Rural communities around the lakes of the Rift Valley region depend heavily on poultry to survive, and live in close contact with both domestic and migratory birds.

The FAO's chief veterinary officer, Joseph Domenech, said on 19 October that African countries should be given international assistance to help them look out for the virus and control any outbreaks. He warned that if the virus becomes endemic in Africa, the chances of it mutating to spread between humans, potentially triggering a pandemic, will increase.

But the most immediate threat is the economic loss that will result if large numbers of poultry succumb to the disease or have to be culled. "Losing poultry would have a devastating effect on livelihoods in the area," says Lea Borkenhagen, sustainable-living development manager at the charity Oxfam, UK. "Women in particular would be affected, as poultry represent the only assets they can possess."

Tadelle Dessie, a poultry researcher at the International Livestock Research Institute in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, agrees. Earlier this year he travelled to Vietnam where more than 40 people have been killed by H5N1, and spent time with experts working to contain the virus and develop systems to spot it early. "The situation in Africa could be worse," he warns.

There is concern that, so far, not enough is being done to look out for bird flu in the region. "We need to raise awareness of the risks," says Hagemeijer. "Experts know about it, but there is no wider coordination." He is currently travelling in Africa as part of an effort by Wetlands International to establish a network of people monitoring water birds for signs of the disease.

Few countries in the area have systems in place to test for H5N1. And efforts to control outbreaks would be hampered by the difficult terrain in remote communities around the region's lakes, as well as by the low level of education across the region. "Our estimate for the Rift Valley is that literacy rates are between 10% and 40%, with women at the lower end," says Borkenhagen. "That's much lower than in countries such as Vietnam, so it will be hard for people to take on the kind of information that will have to be given."

Dessie says his attempts to get the Ethiopian government to acknowledge the problem have so far been unsuccessful, but that he hopes the FAO's warning will lead to action.

In response to Domenech's statement, Kenya, Sudan and Tanzania have all imposed restrictions on poultry imports, and Tanzanian livestock officials say they are teaching people in wetland areas to keep poultry away from wild birds. East African nations will meet next month in Rwanda to develop a regional strategy to handle the threat of bird flu.