Mukhtaran Bibi / Mukhtar Mai / Mukhtiar

See just this Post & Comments / 0 Comments so far / Post a Comment / HomeI saw this story years ago and it is still going on for her - and not all for the best by the look of it. I thought it was a telling point that she "could not afford" to hire contract killers, and that the Justice System had raped her a second time. Well, that's what Justice Systems do, doesn't she know?! Putting on a bit of weight and now she is a darling of the Paris lefties (is that it?); written a book and what not. I liked her school idea and was following along with that ... When they start comparing you to Martin Luther King Junior you had better watch out.

Spiegel: February 6, 2006, Village Justice in Pakistan, A Court Ordered Gang Rape, Uwe Buse

Wikipedia: Mukhtaran Bibi

The Hindu: Inspiration from Pakistan

Mukhtar Mai, the daughter of a Pakistani farmer, thought she was apologizing for the misdeeds of her brother. Instead, she was gang raped by men in her village. After the rape, Mai contemplated suicide. Today she is likened to Martin Luther King, Jr.

The police officers stationed along the only access road to her parents' farm check everyone who wants to visit Mukhtar Mai. They ask to see passports, they write down names and they even track down visitors in their hotels for further interrogation.

The officers are there to protect Mukhtar Mai, the daughter of farmer Ghulan Farid Jat, but her new freedom sometimes feels more like imprisonment. Whenever she embarks on one of her trips outside Pakistan, her red Nissan gets a police escort all the way to the airport in Islamabad. When she leaves her parents' farm to run errands closer to home, police officers on motorcycles lead the way, shooing donkey carts, bicyclists and busses from the street.

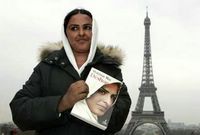

And her trips outside Pakistan are frequent. Indeed, Mai has just returned from a trip which took her to Paris, New York and Las Vegas. She met with the French foreign minister, unveiled her autobiography in Paris, shook hands with United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan and posed for photos with actress Glenn Close. This is the new life of Mukhtar Mai.

Now, though, she sits in her parents' house, where the kitchen is a fire pit in the courtyard, and where she shares a room with five sisters and cousins. They sleep on mattresses, which they push aside every morning. Mukhtar Mai wears a chador, even at night. She finds jeans uncomfortable and tight-fitting clothes inappropriate.

Atoning for her brother's sins

One of her sisters brings in an iron bowl filled with glowing coals and places it on the floor. It's a cold night, and her parents' farm is a simple affair on the outskirts of Meerwala, a village in eastern Pakistan. The drinking water comes from a well and there is no electricity. It's the home of a family that lives in much the same way as many others in Meerwala: poor, honest and far from influential. It's the house where Mukhtar Mai spent her first life.

That life ended on a day in June, three and a half years ago. The sun had already set as Mai was preparing to leave her parents' house. She put on a pair of shoes over her bare feet, knowing that she would soon be walking on an unpaved road. Then she left the house, together with her father, an uncle and a family friend.

Mai's destination on that evening was the neighboring house. The two properties are separated by a field, but there is no direct route. To reach the farm of the Mastoi family, Mai and her companions first had to walk to the main road and then double back to the house. Long before they reached the house, they could hear the excited voices of the men waiting for them. Mai had a duty to fulfill.

It was a duty which had been given her by her father. According to an age-old custom that predates Islam itself, women, the guardians of life, are required to apologize on behalf of their families for injustices committed by other members of their families. In this case, Mai was the chosen one. Her task was to beg forgiveness from the neighbor, the Mastoi family, publicly and on behalf of her brother, the accused. In return, the patriarch of the Mastoi family was to accept her apology, also in public, and abandon any further claims to revenge. This, at least, was what the "panchayat," or village court, had decided, according to the messenger the court had sent to the family. The decision reflects a practice that has successfully been used for centuries to maintain social order in countless other Pakistani villages.

Mai's brother Shakoor was accused of having raped a daughter of the Mastoi family in a sugarcane field, at noon that same day. The daughter's name is Salma. Mai knew her, and she couldn't image that there was any truth to the accusation. Salma was 25 at the time, a grown woman. Mai's brother was 12, a child. But it wasn't Mai's place to express her doubts, not to the accusers, not to her father and not to her brothers. She was a woman and her duty was to be silent and obedient. That's what tradition called for, and Mai obeyed.

"Do what you want with her"

The men of the village had pronounced their sentence that afternoon, though neither Shakoor, nor anyone else in the family, was ever questioned. But Mai's father didn't question the decision -- he merely ordered his eldest daughter to get ready.

As many as 150 men were waiting for Mai at the Mastoi farm. The light of a petroleum lamp hanging above their heads revealed that many of the men were carrying guns. The woman they saw approaching was stocky and round-faced -- May had been married for seven years by that time, but she had yet to give her husband a single child. The men in the village, of course, were aware of this. Mai, they figured, was probably barren and good for little more than working as a laborer.

May, carrying a shawl and a Koran in her hands, walked the last few steps alone.

She stood in front of the patriarch, Faiz Mohammed Mastoi, a man larger and heavier than she is and, on that evening, carrying a pump gun. As a sign of her humility, she spread out her shawl, recited a verse from the Koran and placed her hand on the book of books. Mai kept her head bowed, as is considered proper for a woman, and then she said: "If my brother Shakoor has committed an injustice, I beg for forgiveness in his place."

Faiz Mastoi listened, silently, but then he shook his head, seething with rage, and Mai began to pray. She heard Mastoi say: "Do what you want with her." Mai felt her legs giving way, felt hands touching her body and heard the sounds of ripping material and howling men. They carried Mai into a stable, where they pushed her onto a dirt floor and raped her.

Mai spent the next few days alone in her parents' house. Her father didn't report the incident to the police, nor was a doctor summoned to tend to her wounds. Mai knew what was expected of women in her situation. She was expected to commit suicide -- to restore her family's honor.

Today, three and a half years later, Mukhtar Mai is still alive. She no longer lives in the Middle Ages. She lives in the 21st century, traveling around the world alone, without her father or her brothers. Her father continues to work in the fields and in a nearby sawmill and whenever journalists visit Mai, her father stands silently next to his daughter, looking like an extra in a production he no longer understands.

Despite Mai's fame, her parents' house still has no indoor oven. Mukhtar Mai is against leading a more comfortable life in the belief that every appliance, piece of furniture or ring on her fingers would only provide her enemies with proof that she is an avaricious, westernized slut.

Gang rape by court order

Some call her that because they resent the fact that Mai is the only member of her family who has a car, a mobile phone and a bank account in her own name. They also resent the fact that she has changed. She is still quiet, not out of shame or humility, but because it takes time and energy to understand and process everything she has seen in the past three years.

During her travels, Mai has met with women who are successfully fighting for their rights and for independent lives. These women do as they wish, not as they are told by a man. They go where they please, speak with whomever they wish to speak, and wear whatever suits their fancy. Mai has met these women -- in Madrid, Paris and New York -- and during these encounters she discovered that she isn't the only woman in Pakistan who was abused to settle a family score.

Human rights organizations have learned that there were 20 similar cases in Pakistan in June 2002 alone, the month in which Mai was raped. But none of these cases was legitimized by a village court. Apparently, Mai's case was the first in which a village court ordered a public gang rape.

Mai learned these things from members of the international women's rights movement -- indeed, she herself has since become a global icon of the women's rights movement. Her name is often mentioned in the same sentence with those of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

Mai's life isn't the only thing that's been altered -- she has also transformed her village with the proceeds from her book and with donations from all over the world. Before Mai's martyrdom, Meerwala had no school and no electricity, and its roads were narrow and extraordinarily rough. Today the village has two schools, one for boys and one -- unheard of in this remote region -- for girls; the streets have been widened and they are flanked by power lines; some houses even have television.

Had she done something wrong?

All of this is the result of suffering inflicted on Mukhtar Mai in the name of revenge and tradition, in the name of age-old customs and practices. Mukhtar Mai's sacrifice was meant to secure these customs and this isolated world and prevent western values from contaminating the village and, of course, its purpose was to make sure that the men of Meerwala would continue to enjoy the life to which they were accustomed -- as masters of their universe, as men who beat their wives and sell their daughters whenever it suits their fancy.

Mai's death was supposed to ensure the continued existence of this world. But instead of submitting to her fate, Mai managed to turn her world upside down.

After the rape, Mai spent days and nights lying on a mattress in her room, thinking of suicide and quarreling with her god. What had she done wrong, she wanted to know? She was a simple farmer's daughter and had never attended school. She was illiterate. Eager for at least some challenge, she had learned the Koran by heart, each of its 114 verses, and had even recited them to the girls in the village. Had she done something wrong?

But instead of finding answers, Mai discovered her own rage -- and her rage was directed at men. She knew the sensation from earlier days when her father or her brothers had treated her unfairly. At the time, she had suppressed the emotion because rage was something to which only men were entitled, but suddenly the thought occurred to her that she too could be angry. What could be so wrong about that? After all, doesn't everything, including rage, come from Allah? Rage was a good feeling, and suddenly revenge, not suicide, seemed to be a worthwhile goal.

But how could she take revenge? She lacked the connections and the money to hire contract killers. Plus, the police in Meerwala paid more attention to the powerful Mastoi clan than to the letter of the law.

Perhaps it was one of the village judges who told her story, or someone from the Mastoi family seeking to show off, or even one of the onlookers who didn't participate in the rape. In any case, a few journalists caught wind of the rumors and soon Mukhtar Mai's story began surfacing in articles in the local press, first in Multan and then in Lahore. Human rights activists began holding press conferences to express their outrage and more articles were published, finally forcing the police to take action.

"Bribery" and "political influence"

At first local officials tried to cover up the story, falsifying Mai's statement and putting her under pressure. But even these efforts found their way into the press, first regionally, then nationally and finally on the BBC. By then the case was no longer just a crime, but a political issue, an issue in which nothing less than Pakistan's reputation in the world was at stake.

Mai played no part in these developments. Instead, media-savvy human rights activists controlled the campaign, while Mai's contribution was her face and her story. She agreed to be examined by a doctor, who documented her injuries. She forced herself to tell the entire story to a judge, a man -- she even told the things that she hadn't even dared tell her mother. And she began to become accustomed to her new status, her new life as a national symbol of a modern Pakistan -- even as she also knew that this new life meant she would be exposed herself to threats by religious fanatics.

The first trial took place in Dera Ghazi Khan, a city three hours by car from Meerwala. Five eyewitnesses and a medical expert confirmed the rape. Two months after the incident, the judge pronounced his sentence in a special night session of the court. The four rapists and the two judges on the village court were sentenced to death by hanging and to a fine of 50,000 rupees, or about €700. Eight other defendants, who had threatened Mai's father with their weapons while she was being raped, were acquitted. Mai celebrated her victory at a press conference, but the Mastoi family filed an appeal and the case was referred to the High Court in Multan. The men who had been sentenced remained in custody.

This time it took two and a half years for the court to issue its ruling. On March 3, 2005, five of those who had been sentenced to death were acquitted and one was sentenced to life in prison. The ruling caused such an uproar in the courtroom that security guards had to restore order. The country's newspapers were filled with stories of "bribery" and "political influence-peddling."

Mai told journalists that she had been raped a second time, this time by Pakistan's judicial system. She announced her intention to appeal the verdict, denied that she planned to go into exile and was taken home by a police escort. A few days later, 3,000 protestors marched through Multan and demanded justice for Mukhtar Mai and women's rights organizations staged a sit-in in front of the city's prison. Officials at the country's interior ministry feared the possibility of attacks, both on Mai and her supporters and on members of the rapists' families. When the men who had been acquitted were released on March 14, 2005, 15 police cars were stationed in front of the family's farm in Meerwala. The province was on the brink of turmoil.

On the advice of human rights activists, Mai traveled to the Pakistani capital Islamabad and demanded to meet with the interior minister. She was received and was assured that the minister would use an exceptional provision of the Pakistani legal system to put the perpetrators back behind bars. Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf also met with Mai and, in her presence, telephoned the provincial governor to ensure that the men who had been released were back in custody.

On June 28, 2005, Pakistan's Supreme Court declared the acquittals invalid and ordered a third and last trial. A date for that trial has not yet been set.

In Pakistan, Mai is now protected against potential assassins and guarded so that the government can keep tabs on her. She has become part of the country's political elite, praised by liberals and cursed by fundamentalists.

Two new schools

Next to her house, workers are building a red and white brick addition to the girls' school. Mai paid for the school, and for the building that houses the boys' school a few hundred meters away, but the money ultimately came from international donors. The Pakistani government does help out -- it pays the salaries of the male teachers in the boys' school. Over at the girls' school, though, Mai herself has to cough up the payroll money. Even with the money she has made from her autobiography, though, it is hardly enough, and maintaining the flow of donations so that her school can continue to operate is a major challenge. She also has a number of other projects planned -- a hospital and a mobile treatment center for abused women, for example. She needs funding to make them a reality.

Aside from leapfrogging over centuries in the space of three years, Mai has also had to familiarize herself with the rules of the international business of making the world a better place. She has had to learn that it's a tough and competitive business, and that she has no control over her position in this part of the global world.

A few months ago her bank account was empty and donations had slowed to a sporadic trickle, forcing her to sell her jewelry, a pair of earrings. Since then, she says, the weight of responsibility has become almost unbearable. She has trouble sleeping, more so than in her first life. Pakistan is rife with rumors about Mukhtar Mai -- that she's a dollar millionaire and that, although she may be incapable of giving men children, she is able to provide them with American citizenship.

The chairman of a regional party is scheduled to visit Mai on this afternoon. Colonel Abdul Jabbar Abbasi arrives in a motorcade, surrounded by half a dozen Pakistani journalists. He is a portly man who immediately proceeds to talk about himself -- his successes, his plans, his travels.

During the meal, he boasts that he managed to get the better of a "negro" in New York who had attempted to rob him. He poses briefly next to Mai, calling her "a welcome addition to my party's convention" as he condescendingly runs his hand across her hair to the clicking of the journalists' cameras. Mai attempts to dodge the man's hand but Colonel Abdul Jabbar Abbasi doesn't seem to have grasped that he isn't stroking the head of an accomplice, but of an adversary who plans to deprive men like him of their power.

Praying for the death of her rapists

Mukhtar Mai prays every day for a quick trial, for the death of her rapists and for more donations. But there is one request that she never forgets to mention in her prayers: She asks Allah to grant Abdul Razzak, the mullah of Meerwala, the strength to stand up to his difficult task before the court the next time the state tries her case. Mai doesn't want to see Razzak fail once again, as he did in the village court when facing the powerful men of the Mastoi clan.

Razzak has been the mullah in Meerwala for many years. He lives in a modest house behind the mosque, he has no great aspirations to acquire material possessions, and he rarely raises his voice. Razzak believes that his community should respect the rules of the Koran for sensible reasons, not out of fear of the wrath of God. Razzak is a thoughtful man, and he wouldn't have expected that he would ever face a moral dilemma as a result.

He sits in a chair twisting a cup of tea with buffalo milk between his fingers. Midday prayers have just ended, and the faithful have followed him into his house after hearing that journalists are waiting for their mullah. A dozen men stand in the room, leaning against the wall, while others crowd into the doorway -- the scene is reminiscent of a tribunal with Razzak in the dock.

He was one of the three judges on the village court that imposed the first sentence on Mukhtar Mai's family three years ago. It wasn't the first time Razzak assumed this task; in fact, he was traditionally one of the village's decision-makers.

Faiz Mastoi was both the second judge and the prosecutor. It was a problematic situation, but Faiz Mastoi refused to recuse himself and no one else dared to challenge him. The third judge was a member of another clan who was not directly involved in the matter. The judges were surrounded by the rest of the men, who can make suggestions and demand penalties in such tribunals, although the judges are the ones who issue the ruling.

The weak mullah

Mullah Razzak recalls that it was a heated discussion. Most of the men were relatives of the alleged victim -- her brothers, cousins and uncles -- and they wanted revenge, not justice. They demanded that the family of the alleged rapist supply a woman, who would then also be raped.

The suggestion angered Razzak. Such action is not justified by any verse or syllable in the Koran and Razzak pleaded for a solution that would involve reconciliation between the parties, proposing that a woman from the alleged rapist's family publicly apologize for her brother's behavior. He also suggested that marriages between the two feuding families could help restore the peace. But the Mastoi family rejected Razzak's proposal, demanding revenge instead.

After announcing that he opposed the Mastoi family's demands, Razzak realized that his proposal had failed and left the village tribunal. But he didn't head to the house of Mukhtar Mai to warn her, nor did he head to the police to notify them of what was about to happen. Instead, Razzak went home to pray.

"I should have been more courageous," Razzak says today. A few men in the room nod their heads, but not the majority. Those who don't nod are the men who want their old world back, a world in which they -- the men -- are in charge in Meerwala, and not Mukhtar Mai.

Now Razzak will serve -- for the first time -- as the key witness for the prosecution in the next trial against Mukhtar Mai's rapists. He will report on what he saw and heard, and the people for the Mastoi clan will call him a liar, a man whose only goal is to destroy their families.

A mother of rapists

Taj Mastoi is the mother of two of Mukhtar Mai's rapists, and she is also Mai's closest neighbor. She lives at the scene of the crime, and yet she denies that it ever happened -- and she also claims that the village tribunal never existed, and that the only truth is that Salma, the girl, was raped by Mai's younger brother. Everything else, she says, is nonsense.

The matriarch stands with her back against the wall as she speaks -- a small, bitter woman who has spent the past three years cooking meals for her sons in prison and taking care of her grandchildren. She was forced to sell much of her furniture over the years and her house is falling apart. Now all she can do is wait -- possibly for the death of her sons. When she looks out the window, she sees Mukhtar Mai's farm. On the left is the new school and on the right the new police station Mai is having built for her own protection.

At night fluorescent tubes and light bulbs illuminate the construction site, which is patrolled by police officers shining the beams of their halogen flashlights into the night.

Taj Mastoi's house is dark. She can't afford the electricity hookup. She curses Mukhtar Mai.

Tags: Mukhtiar, Pakistan.